“Values.”

It’s a complicated concept in philosophy.

At least, it used to be.

But now that you’ve found this post, philosophical values are about to become crystal clear.

I’m going to show you everything you need to know about values and ethics, including some examples and links to great resources.

You’ll also discover how values come about in the first place.

They’re definitely about a lot more than philosophy, though philosophy has long been involved in helping us understand them.

So if you’re ready to learn about whether or not values are objectively true or created by humans, let’s dive into this fascinating topic.

What Are Values?

Values in philosophy boil down to what is good, bad or advantageous.

We value things all the time, including ourselves. When Voltaire, for example, said that “we are not as good as the Romans” in his comments on common sense, he made a value judgment.

Values can also be prospective in nature. We draw upon them when we talk about what we think “ought” to be. When communicating with others about moral oughts, we’re usually drawing upon how we think people currently assess the world.

The fact that we often try to shape or persuade the values of others suggests that many values are created.

Friedrich Nietzsche famously claimed in On the Genealogy of Morality that humans are a low-value species. In fact, he predicted that if we didn’t pay more attention to “inventing” our values, we would soon have no values at all.

More recently, Bryan Van Norden has suggested that our current scholarly systems are “bad” because they do not include enough global variety when it comes to philosophy.

He is making an “ought” argument which suggests, rather persuasively, that by broadening our range, our understanding of philosophy will be better.

I agree, and understanding values is as simple as that. It is bad not to have a greater understanding and more desirable to expand our comprehension through extended exposure to more ideas.

How Philosophy Informs Your Values

If we assume that values are created or invented, then philosophy informs your values in a number of ways:

- Educating you about their existence

- Giving you an overview of the kinds of values that exist

- Persuading you about what your values “ought” to be

- Exposing you to ideas about values and how to improve or change those that you have for better values

To understand how this process works, let’s look at some specific values and learn how philosophy and values interact.

One & Many

The idea that you are an individual shapes many of your values. You believe yourself to be physically and mentally whole and because you value this wholeness, you take steps to protect it.

But when you switch your thinking to how you as an individual operate within a larger society, your values may shift.

For example, you may be willing to put aside some of your self concern in order to get along with society. Many people understand the role of taxation, traffic laws and give to charity. They are able to value other people in addition to valuing themselves.

It’s not just reading philosophy that will shape how you view your value against the values of society as a whole. Religious upbringing and general education also shape how people balance their values and ethics.

In some traditions, such as Jainism, the entire universe is taken into consideration.

Morality & Immorality

The question of morality affects us all each and every day.

Take entertainment, for example.

Some people feel that portraying or saying certain things in a story is immoral. Others say that restricting the ability to represent the very same things is immoral.

It’s not easy to sort such issues out.

However, with self-awareness of your own values and the values of others, much more intelligent conversations can take place.

One interesting factor in this category is the notion of immorality caused by ignorance. Whereas some say it is immoral to be ignorant, others have thought this issue is only a problem if you are unwilling to correct your ignorance.

Freedom vs. Compulsion

Most of us like to move freely in the world and think the thoughts we want to think, right?

Wrong. Not everyone shares this value.

Some political and religious groups do not place a premium on your freedom of thought. They even go out of the way to remove media while populating the airwaves and the Internet with propaganda and/or psychological operations.

Issues related to democracy and other forms of governance emerge when we examine our values related to freedom. Many people would do well to prioritize their understanding of this category because it is very easy to mobilize large groups, and it often happens to individuals outside of their awareness.

And because they don’t have a well-established set of values, they wind up supporting lies they’ve mistaken for truths. Worse, many people voluntarily give up their freedom and are so blind to what’s really going on, they express gratitude for the opportunity to lock the chains around their own wrists.

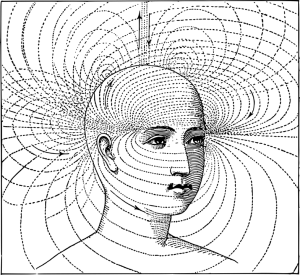

Art and Aesthetics

Most people know what art is.

But what about when something new, radical and strange appears? It doesn’t seem to have a message you understand and violates your sense of taste. Is it still “art”?

The question might not have an easy answer. And as Nigel Warburton suggests in Philosophy: The Basics, there might not be an answer at all. That is because it is futile to look for a common denominator amongst all types of arts.

Surrealism, for example, is downright irrational in many cases. Not all people find it appealing, nor are they willing to develop the aesthetic vocabulary needed to appreciate what might be going on with such art.

But most of us do have a sense of taste, which boils down to aesthetics. We value features of the world such as beauty, depth, representation and abstraction. And when we reflect on what our personal values related to art and aesthetics are, we are doing philosophy.

If we don’t think about our aesthetic values, we might be making the mistake of allowing institutions to do that for us through persuasion and propaganda.

Scientific Knowledge vs. Superstition

Most of us value many of the things science has helped us either identify, shape or create, everything from vitamin supplements to virtual reality.

But some people value science so highly that they seek to suppress religious intuitions in either themselves or others. Richard Dawkins is one such “militant atheist.” I was like that myself for a long time as discussed in this TEDx Talk:

But polemics against religion and superstition prevent us from even perceiving the different values contained in the difference between the fields. As Adrian Moore suggests, we need to have those conversations so that we can actually do philosophy.

That said, religions institutes that invent values should not be given a free pass.

Knowledge of the Catholic church and its history, for example, reveals many standards it has clearly invented and reinvented over time. This process has worked because of collective, institutional institutions that only worked because of how the church suppressed dissenting and innovative voices like those of Galileo and Giordano Bruno.

Does Philosophy Have Value?

Now that we have a sense of what philosophical values are, the question remains: What of philosophy itself? Does it have a value?

I would say absolutely yes.

Philosophy is what we do when we don’t have a science to address our questions about the nature of being.

And it helps us ask questions that expose precisely how values are invented by both individuals and institutions.

But there’s also a very real sense in which values are discovered too.

Discovery comes through research, reflection and conversation.

This ties in with something I’ve interpreted from reading Nietzsche and found echoed in scholars like Elijah Milgram.

Values have value only when they are embedded in a perspective.

And because change seems to be the only constant, values can only be effective when we engage them as a process.

And because our values are always subject to change, it’s important to at least try to understand how they are discovered and produced by our societies.

Only then do we have a shot at bettering them.